Chancroid

Soft chancre; Ulcus molle; Sexually transmitted disease - chancroid; STD - chancroid; Sexually transmitted infection - chancroid; STI - chancroid

Chancroid is a bacterial infection that is spread through sexual contact.

Causes

Chancroid is caused by a bacterium called Haemophilus ducreyi.

The infection is found in many parts of the world, such as Africa and southwest Asia. The infection is uncommon in the United States. Most people in the United States who are diagnosed with chancroid get it outside the country in areas where the infection is more common.

Symptoms

Within 1 day to 2 weeks after becoming infected, a person will get a small bump on the genitals. The bump becomes an ulcer within a day after it first appears. The ulcer:

- Ranges in size from 1/8 inch to 2 inches (3 millimeters to 5 centimeters) in diameter

- Is painful

- Is soft

- Has sharply defined borders

- Has a base that is covered with a gray or yellowish-gray material

- Has a base that bleeds easily if it is bumped or scraped

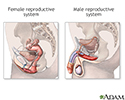

About one half of infected men have only a single ulcer. Women often have 4 or more ulcers. The ulcers appear in specific locations.

Common locations in men are:

- Foreskin

- Groove behind the head of the penis

- Shaft of the penis

- Head of the penis

- Opening of the penis

- Scrotum

In women, the most common location for ulcers is the outer lips of the vagina (labia majora). "Kissing ulcers" may develop. Kissing ulcers are those that occur on opposite surfaces of the labia.

Ulcers also may form on the:

- Inner vagina lips (labia minora)

- Area between the genitals and the anus (perineal area)

- Inner thighs

The most common symptoms in women are pain with urination and intercourse.

The ulcer may look like the sore of primary syphilis (chancre).

About one half of the people who are infected with a chancroid develop enlarged lymph nodes in the groin.

In one half of people who have swelling of the groin lymph nodes, the nodes break through the skin and cause draining abscesses. The swollen lymph nodes and abscesses are also called buboes.

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider diagnoses chancroid by:

- Looking at the ulcer(s)

- Checking for swollen lymph nodes

- Testing (ruling out) for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

There is no blood test for chancroid.

Treatment

The infection is treated with antibiotics including ceftriaxone and azithromycin. Large lymph node swellings may need to be drained, either with a needle or local surgery.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Chancroid can get better on its own. Some people have months of painful ulcers and draining. Antibiotic treatment often clears up the lesions quickly with very little scarring.

Possible Complications

Complications include urethral fistulas and scars on the foreskin of the penis in uncircumcised males. People with chancroid should also be checked for other sexually transmitted infections, including but not limited to syphilis, HIV, and genital herpes.

In people with HIV, chancroid may take much longer to heal.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider for an appointment if:

- You have symptoms of chancroid.

- You have had sexual contact with a person who you know has an STI.

- You have engaged in high-risk sexual practices.

Prevention

Chancroid is spread by sexual contact with an infected person. Avoiding all forms of sexual activity is the only absolute way to prevent an STI.

However, safer sex behaviors may reduce your risk. The proper use of condoms, either the male or female type, greatly decreases the risk of catching an STI. You need to wear the condom from the beginning to the end of each sexual activity.

References

Micheletti RG, James WD, Elston DM, McMahon PJ. Bacterial infections. In: James WD, Elston DM, McMahon PJ, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin Clinical Atlas. 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2023:chap 14.

Murphy TF. Haemophilus species including H. influenzae and H. ducreyi (chancroid). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 225.

Review Date: 8/26/2023