Neurosyphilis

Syphilis - neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis is a bacterial infection of the brain or spinal cord. It usually occurs in people who have had untreated syphilis for many years.

Causes

Neurosyphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum bacteria. Neurosyphilis usually occurs about 10 to 20 years after a person is first infected with syphilis. Not everyone who has syphilis develops this complication.

There are four different forms of neurosyphilis:

- Asymptomatic (most common form)

- General paresis

- Meningovascular

- Tabes dorsalis

Asymptomatic neurosyphilis occurs before symptomatic syphilis. Asymptomatic means there aren't any symptoms.

Symptoms

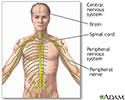

Symptoms usually affect the nervous system. Depending on the form of neurosyphilis, symptoms may include any of the following:

- Abnormal walk (gait), or unable to walk

- Numbness in the toes, feet, or legs

- Problems with thinking, such as confusion or poor concentration

- Mental problems, such as depression or irritability

- Headache, seizures, or stiff neck

- Loss of bladder control (incontinence)

- Tremors, or weakness

- Visual problems, even blindness

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will do a physical examination and may find the following:

- Abnormal reflexes

- Muscle atrophy

- Muscle contractions

- Mental changes

Blood tests can be done to detect substances produced by the bacteria that cause syphilis, this includes:

- Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA)

- Venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS)

- Rapid plasma reagin (RPR)

With neurosyphilis, it is important to test the spinal fluid for signs of syphilis.

Tests to look for problems with the nervous system may include:

- Cerebral angiogram

- Head CT scan

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

- MRI scan of the brain, brainstem, or spinal cord

Treatment

The antibiotic penicillin is used to treat neurosyphilis. It can be given in different ways:

- Injected into a vein several times a day for 10 to 14 days.

- By mouth 4 times a day, combined with daily muscle injections, both taken for 10 to 14 days.

You must have follow-up blood tests at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months to make sure the infection is gone. You will need follow-up lumbar punctures for CSF analysis every 6 months. If you have HIV/AIDS or another medical condition, your follow-up schedule may be different.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Neurosyphilis is a life-threatening complication of syphilis. How well you do depends on how severe the neurosyphilis is before treatment. The goal of treatment is to prevent further deterioration. Many of these changes are not reversible.

Possible Complications

The symptoms can slowly worsen.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have had syphilis in the past and now have signs of nervous system problems.

Prevention

Prompt diagnosis and treatment of the original syphilis infection can prevent neurosyphilis.

References

Euerle BD. Spinal puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In: Roberts JR, Custalow CB, Thomsen TW, eds. Roberts and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine and Acute Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 60.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke website. Neurosyphilis. www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/neurosyphilis. Updated July 19, 2024. Accessed September 8, 2024.

Radolf JD, Tramont EC, Salazar JC. Syphilis (Treponema pallidum). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 237.

Review Date: 12/4/2022