Absent pulmonary valve

Absent pulmonary valve syndrome; Congenital absence of the pulmonary valve; Pulmonary valve agenesis; Cyanotic heart disease - pulmonary valve; Congenital heart disease - pulmonary valve; Birth defect heart - pulmonary valve

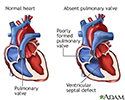

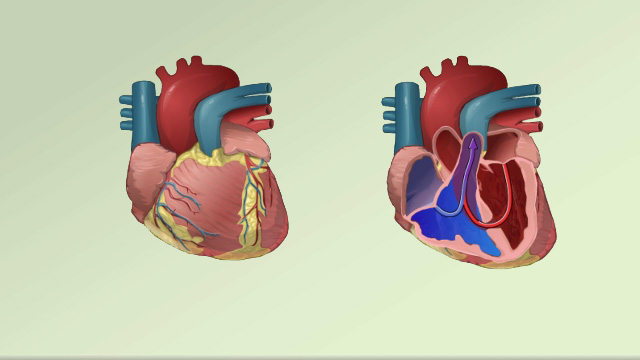

Absent pulmonary valve is a rare defect in which the pulmonary valve is either missing or poorly formed. Oxygen-poor blood flows through this valve from the heart to the lungs, where it picks up fresh oxygen. This condition is present at birth (congenital).

Causes

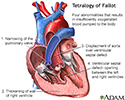

Absent pulmonary valve occurs when the pulmonary valve does not form or develop properly while the baby is in the mother's womb. When present, it often occurs as part of a heart condition called tetralogy of Fallot. It is found in about 3% to 6% of people who have tetralogy of Fallot.

When the pulmonary valve is missing or does not work well, blood does not flow efficiently to the lungs to get enough oxygen.

In most cases, there is also a hole between the left and right ventricles of the heart (ventricular septal defect). This defect will also lead to low-oxygen blood being pumped out to the body.

The skin will have a blue appearance (cyanosis), because the body's blood contains a low amount of oxygen.

Absent pulmonary valve also results in very enlarged (dilated) branch pulmonary arteries (the arteries that carry blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen). They can become so enlarged that they press on the tubes that bring the oxygen into the lungs (bronchi). This causes breathing problems.

Other heart defects that can occur with absent pulmonary valve include:

- Abnormal tricuspid valve

- Atrial septal defect

- Double outlet right ventricle

- Ductus arteriosis

- Endocardial cushion defect

- Marfan syndrome

- Tricuspid atresia

- Absent left pulmonary artery

Heart problems that occur with absent pulmonary valve may be due to defects in certain genes.

Symptoms

Symptoms can vary depending on which other defects the infant has, but may include:

- Blue coloring to the skin (cyanosis)

- Coughing

- Failure to thrive

- Poor appetite

- Rapid breathing

- Respiratory failure

- Wheezing

Exams and Tests

Absent pulmonary valve may be diagnosed before the baby is born with a test that uses sound waves to create an image of the heart (echocardiogram).

During an exam, the health care provider may hear a murmur in the infant's chest.

Tests for absent pulmonary valve include:

- Heart CT scan

- Chest x-ray

- Echocardiogram

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) test to measure the electrical activity of the heart

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the heart

Treatment

Infants who have respiratory symptoms typically need surgery early. Infants without severe symptoms most often have surgery within the first 3 to 6 months of life or later.

Depending on the type of other heart defects the infant has, surgery may involve:

- Closing the hole in the wall between the left and right ventricles of the heart (ventricular septal defect)

- Closing a blood vessel that connects the aorta to the pulmonary artery (ductus arteriosis)

- Enlarging the flow from the right ventricle to the lungs

Types of surgery for absent pulmonary valve include:

- Moving the pulmonary artery to the front of the aorta and away from the airways

- Rebuilding the artery wall in the lungs to reduce pressure on the airways (pulmonary plication and reduction arterioplasty)

- Rebuilding the windpipe and breathing tubes to the lungs

- Replacing the abnormal pulmonary valve with one taken from human or animal tissue

Infants with severe breathing symptoms may need to get oxygen or be placed on a breathing machine (ventilator) before and after surgery.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Without surgery, there may be a risk for serious consequences.

In many cases, surgery can treat the condition and relieve symptoms. Outcomes are most often very good.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Brain infection (abscess)

- Lung collapse (atelectasis)

- Pneumonia

- Right-sided heart failure

- Stroke

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if your infant has symptoms of absent pulmonary valve. If you have a family history of heart defects, talk to your provider before or during pregnancy.

Prevention

Although there is no way to prevent this condition, families may be evaluated to determine their risk for congenital defects.

References

Bernstein D. General principles of treatment of congenital heart disease. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 461.

Estevez NG, Ansah DA. Congenital heart disease. In: Gleason CA, Sawyer T, eds. Avery's Diseases of the Newborn. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 50.

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM. Acyanotic congenital heart disease: regurgitant lesions. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 455.

Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM. Cyanotic congenital heart lesions: lesions associated with decreased pulmonary blood flow. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 457.

Valente AM, Dorfman AL, Babu-Narayan SV, Krieger EV. Congenital heart disease in the adolescent and adult. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 82.

Review Date: 2/27/2024