Hydrocephalus

Water on the brain

Hydrocephalus is a buildup of fluid inside the skull that leads to the brain pushing against the skull.

Hydrocephalus means "water on the brain."

Causes

Hydrocephalus is due to a problem with the flow of the fluid that surrounds the brain. This fluid is called the cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF. The fluid surrounds the brain and spinal cord and helps cushion the brain.

CSF normally moves through the brain and around the spinal cord, and then is absorbed into the bloodstream. CSF levels in the brain can rise if:

- The flow of CSF is blocked.

- The fluid does not get properly absorbed into the blood.

- The brain makes too much of the fluid.

Too much CSF puts pressure on the brain. This pushes the brain up against the skull and damages brain tissue.

Hydrocephalus may begin while the baby is growing in the womb. It is common in babies who have a myelomeningocele, a birth defect in which the spinal column does not close properly.

Hydrocephalus may also be due to:

- Genetic defects

- Certain infections during pregnancy

In young children, hydrocephalus may be due to:

- Infections that affect the central nervous system (such as meningitis or encephalitis), especially in infants.

- Bleeding in the brain during or soon after delivery (especially in premature babies).

- Injury before, during, or after childbirth, including subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Tumors of the central nervous system, including the brain or spinal cord.

- Injury or trauma.

Hydrocephalus most often occurs in children. Another type, called normal pressure hydrocephalus, may occur in adults and older people.

Symptoms

Symptoms of hydrocephalus depend on:

- Age

- Amount of brain damage

- What is causing the buildup of CSF fluid

In infants, hydrocephalus causes the fontanelle (soft spot) to bulge and the head to be larger than expected. Early symptoms may also include:

- Eyes that appear to gaze downward

- Irritability

- Seizures

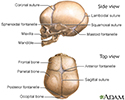

- Separated sutures

- Sleepiness

- Vomiting

Symptoms that may occur in older children can include:

- Brief, shrill, high-pitched cry

- Changes in personality, memory, or the ability to reason or think

- Changes in facial appearance and eye spacing

- Crossed eyes or uncontrolled eye movements

- Difficulty feeding

- Excessive sleepiness

- Headache

- Irritability, poor temper control

- Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence)

- Loss of coordination and trouble walking

- Muscle spasticity (spasm)

- Slow growth (child 0 to 5 years)

- Slow or restricted movement

- Vomiting

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will examine the baby. This may show:

- Stretched or swollen veins on the baby's scalp.

- Abnormal sounds when the provider taps lightly on the skull, suggesting a problem with the skull bones.

- All or part of the head may be larger than normal, often the front part.

- Eyes that look "sunken in."

- White part of the eye appears over the colored area, making it look like a "setting sun."

- Reflexes may be normal.

Repeated head circumference measurements over time may show that the head is getting bigger.

A head CT scan is one of the best tests for identifying hydrocephalus. Other tests that may be done include:

- Arteriography

- Brain scan using radioisotopes

- Cranial ultrasound (an ultrasound of the brain)

- Lumbar puncture and examination of the cerebrospinal fluid (rarely done)

- Skull x-rays

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to reduce or prevent brain damage by improving the flow of CSF.

Surgery may be done to remove a blockage, if possible.

If not, a flexible tube called a shunt may be placed in the brain to reroute the flow of CSF. The shunt sends CSF to another part of the body, such as the belly area, where it can be absorbed.

Other treatments may include:

- Antibiotics if there are signs of infection. Severe infections may require the shunt to be removed.

- A procedure called endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV), which relieves pressure without replacing the shunt.

- Removing or burning away (cauterizing) the parts of the brain that produce CSF.

The child will need regular check-ups to make sure there are no further problems. Tests will be done regularly to check the child's development, and to look for intellectual, neurological, or physical problems.

Visiting nurses, social services, support groups, and local agencies can provide emotional support and help with the care of a child with hydrocephalus who has serious brain damage.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Without treatment, up to 6 in 10 people with hydrocephalus will die. Those who survive will have different amounts of intellectual, physical, and neurological disabilities.

The outlook depends on the cause. Hydrocephalus that is not due to an infection has the best outlook. People with hydrocephalus caused by tumors will often do very poorly.

Most children with hydrocephalus who survive for 1 year will have a fairly normal lifespan.

Possible Complications

The shunt may become blocked. Symptoms of such a blockage include headache and vomiting. Surgeons may be able to help the shunt open without having to replace it.

There may be other problems with the shunt, such as kinking, tube separation, or infection in the area of the shunt.

Other complications may include:

- Complications of surgery

- Infections such as meningitis or encephalitis

- Intellectual impairment

- Nerve damage (decrease in movement, sensation, function)

- Physical disabilities

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Seek medical care right away if your child has any symptoms of this disorder. Call 911 or the local emergency number or go to the emergency room if emergency symptoms occur, such as:

- Breathing problems

- Extreme drowsiness or sleepiness

- Feeding difficulties

- Fever

- High-pitched cry

- No pulse (heartbeat)

- Seizures

- Severe headache

- Stiff neck

- Vomiting

You should also contact your provider if:

- The child has been diagnosed with hydrocephalus, and the condition gets worse.

- You are unable to care for the child at home.

Prevention

Protect the head of an infant or child from injury. Prompt treatment of infections and other disorders associated with hydrocephalus may reduce the risk of developing the disorder.

References

Gunny RS, Saunders DE, Argyropoulou MI. Paediatric neuroradiology. In: Adam A, Dixon AK, Gillard JH, Schaefer-Prokop CM, eds. Grainger & Allison's Diagnostic Radiology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 76.

Ho WS, Kestle JRW. Hydrocephalus in children: etiology and overall management. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 223.

Kinsman SL, Johnston MV. Congenital anomalies of the central nervous system. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 609.

Rosenberg GA. Brain edema and disorders of cerebrospinal fluid circulation. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 88.

Review Date: 11/6/2023

Reviewed By: Neil K. Kaneshiro, MD, MHA, Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.