Pericarditis - constrictive

Constrictive pericarditis

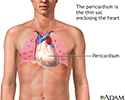

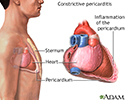

Constrictive pericarditis is a process in which the sac-like covering of the heart (the pericardium) becomes thickened and scarred.

Related conditions include:

- Bacterial pericarditis

- Pericarditis

- Pericarditis after heart attack

Causes

Most of the time, constrictive pericarditis occurs due to things that cause inflammation to develop around the heart, such as:

- Heart surgery

- Radiation therapy to the chest

- Tuberculosis

Less common causes include:

- Abnormal fluid buildup in the covering of the heart. This may occur because of infection or as a complication of surgery.

- Mesothelioma

The condition may also develop without a clear cause.

It is rare in children.

Symptoms

When you have constrictive pericarditis, the inflammation causes the covering of the heart to become thick and rigid. This makes it hard for the heart to expand properly when it beats. As a result, the heart chambers don't fill up with enough blood. Blood backs up behind the heart, causing heart swelling and other symptoms of heart failure.

Symptoms of chronic constrictive pericarditis include:

- Difficulty breathing (dyspnea) that develops slowly and gets worse

- Fatigue

- Long-term swelling (edema) of the legs and ankles

- Swollen abdomen

- Weakness

Exams and Tests

Constrictive pericarditis is very hard to diagnose. Signs and symptoms are similar to other conditions such as restrictive cardiomyopathy and cardiac tamponade. Your health care provider will need to rule out these conditions when making a diagnosis.

A physical exam may show that your neck veins stick out. This indicates increased pressure around the heart. The provider may note weak or distant heart sounds when listening to your chest with a stethoscope. A knocking sound may also be heard.

The physical exam may also reveal liver swelling and fluid in the belly area.

The following tests may be ordered:

- Chest MRI

- Chest CT scan

- Chest x-ray

- Coronary angiography or cardiac catheterization

- ECG

- Echocardiogram

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to improve heart function. The cause must be identified and treated. Depending on the source of the problem, treatment may include anti-inflammatory agents, antibiotics, medicines for tuberculosis, or other treatments.

Diuretics ("water pills") are often used in small doses to help the body remove excess fluid. Pain medicines may be needed for discomfort.

Some people may need to cut down on their activity. A low-sodium diet may also be recommended.

If other methods do not control the problem, surgery called a pericardiectomy may be needed. This involves cutting or removing the scarring and part of the sac-like covering of the heart.

Outlook (Prognosis)

Constrictive pericarditis may be life threatening if untreated.

However, surgery to treat the condition has a high risk for complications. For this reason, it is most often done in people who have severe symptoms.

Possible Complications

Complications may include:

- Heart failure

- Pulmonary edema

- Liver and kidney dysfunction

- Scarring of the heart muscle

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of constrictive pericarditis.

Prevention

In some cases, constrictive pericarditis is not preventable.

However, conditions that can lead to constrictive pericarditis should be properly treated.

References

Hoit BD, Oh JK. Pericardial diseases. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 62.

Jouriles NJ. Pericardial and myocardial disease. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 68.

Lewinter MM, Cremer PC, Klein AL. Pericardial diseases. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Bhatt DL, Solomon SD, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 86.

Review Date: 5/8/2024

Reviewed By: Thomas S. Metkus, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine and Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.