Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Idiopathic diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis; IPF; Pulmonary fibrosis; Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis; CFA; Fibrosing alveolitis; Usual interstitial pneumonitis; UIP

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is scarring or thickening of the lungs without a known cause.

Causes

Health care providers do not know what causes IPF or why some people develop it. Idiopathic means the cause is not known. The condition may be due to the lungs responding to an unknown substance or injury. Genes may play a role in developing IPF. The disease occurs most often in people between 60 and 70 years old. IPF is more common in men than women.

Symptoms

When you have IPF, your lungs become scarred and stiffened. This makes it hard for you to breathe. In most people, IPF gets worse quickly over months or a few years. In others, IPF worsens over a much longer time.

Symptoms may include any of the following:

- Chest pain (sometimes)

- Cough (usually dry)

- Not able to be as active as before

- Shortness of breath during activity (this symptom lasts for months or years, and over time may also occur when at rest)

- Feeling faint

- Gradual weight loss

Exams and Tests

Your provider will do a physical exam and ask about your medical history. You will be asked whether you have been exposed to asbestos or other toxins and if you have been a smoker.

The physical exam may find that you have:

- Abnormal breath sounds called crackles (sounds like Velcro being pulled apart)

- Bluish skin (cyanosis) around the mouth or fingernails due to low oxygen (with advanced disease)

- Enlargement and curving of the fingernail bases, called clubbing

Tests that help diagnose IPF include the following:

- Bronchoscopy

- High resolution chest CT scan (HRCT)

- Chest x-ray

- Echocardiogram

- Measurements of blood oxygen level (arterial blood gases)

- Pulmonary function tests

- 6-minute walk test

- Tests for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or scleroderma

- Open lung (surgical) biopsy

Treatment

There is no known cure for IPF.

Treatment is aimed at relieving symptoms and slowing disease progression:

- Pirfenidone (Esbriet) and nintedanib (Ofev) are two medicines that are used to treat people with IPF. They may help slow lung damage.

- People with low blood oxygen levels will need oxygen support at home.

- Lung rehabilitation will not cure the disease, but it can help people exercise with less difficulty breathing.

Making home and lifestyle changes can help manage breathing symptoms. If you or any family members smoke, now is the time to stop.

A lung transplant may be considered for some people with advanced IPF.

Support Groups

You can ease the stress of illness by joining a support group. Sharing with others who have common experiences and problems can help you not feel alone.

More information and support for people with IPF and their families can be found at:

- Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation -- www.pulmonaryfibrosis.org/patients-caregivers/medical-and-support-resources/find-a-support-group

- American Lung Association -- www.lung.org/better-breathers

Outlook (Prognosis)

IPF may improve or stay stable for a long time with or without treatment. Most people get worse, even with treatment.

When breathing symptoms become more severe, you and your provider should discuss treatments that prolong life, such as lung transplantation. Also discuss advance care planning.

Possible Complications

Complications of IPF may include:

- Abnormally high levels of red blood cells due to low blood oxygen levels

- Collapsed lung

- High blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs

- Respiratory failure

- Cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure)

- Death

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider right away if you have any of the following:

- Breathing that is harder, faster, or shallower (you are unable to take a deep breath)

- Need to lean forward when sitting to breathe comfortably

- Frequent headaches

- Sleepiness or confusion

- Fever

- Dark mucus when you cough

- Blue fingertips or skin around your fingernails

References

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed May 14, 2024.

Raghu G, Martinez FJ. Interstitial lung disease. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 80.

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. PMID: 35486072 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35486072/.

Ryu JH, Selman M, Lee JS, Colby TV, King TE. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King TE, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 89.

Silhan LL, Danoff SK. Nonpharmacologic therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. In: Collard HR, Richeldi L, eds. Interstitial Lung Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 5.

Spirometry - illustration

Spirometry

illustration

Clubbing - illustration

Clubbing

illustration

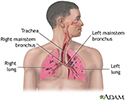

Respiratory system - illustration

Respiratory system

illustration

Review Date: 5/3/2024

Reviewed By: Allen J. Blaivas, DO, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, VA New Jersey Health Care System, Clinical Assistant Professor, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, East Orange, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.