Meningococcal meningitis

Gram negative - meningococcus

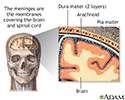

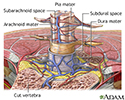

Meningitis is an infection of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. This covering is called the meninges.

Bacteria are one type of germ that can cause meningitis. The meningococcal bacteria are one kind of bacteria that cause meningitis.

Causes

Meningococcal meningitis is caused by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis (also known as meningococcus).

Meningococcus is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis in children and teens. It is a leading cause of bacterial meningitis in adults.

The infection occurs more often in winter or spring. It may cause local epidemics at boarding schools, college dormitories, or military bases.

Risk factors include recent exposure to someone with meningococcal meningitis, complement deficiency, use of eculizumab, spleen removal or a spleen that does not function, and exposure to cigarette smoking.

Symptoms

Symptoms usually come on quickly, and may include:

- Fever and chills

- Mental status changes

- Nausea and vomiting

- Purple, bruise-like areas (purpura)

- Rash, pinpoint red spots (petechiae)

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Severe headache

- Stiff neck

Other symptoms that can occur with this disease:

- Agitation

- Bulging fontanelles in infants

- Decreased consciousness

- Poor feeding or irritability in children

- Rapid breathing

- Unusual posture with the head and neck arched backwards (opisthotonus)

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will perform a physical exam. Questions will focus on symptoms and possible exposure to someone who might have the same symptoms, such as a stiff neck and fever.

If the provider thinks meningitis is possible, a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) will likely be done to obtain a sample of spinal fluid for testing.

Other tests that may be done include:

- Blood culture

- Chest x-ray

- CT scan of the head

- White blood cell (WBC) count

- Gram stain or, other special stains, and culture of the spinal fluid

Treatment

Antibiotics will be started as soon as possible.

- Ceftriaxone is one of the most commonly used antibiotics.

- Penicillin in high doses can be effective for susceptible bacteria.

- If there is an allergy to penicillin, chloramphenicol may be used.

Sometimes, corticosteroids may be given.

People in close contact with someone who have meningococcal meningitis should be given antibiotics to prevent infection.

Such people include:

- Household members

- Roommates in dormitories

- Military personnel who live in close quarters

- Those who come into close and long-term contact with an infected person

Outlook (Prognosis)

Early treatment improves the outcome. Death is possible. Young children and adults over age 50 have the highest risk of death.

Possible Complications

Long-term complications may include:

- Brain damage

- Hearing loss

- Buildup of fluid inside the skull that leads to brain swelling (hydrocephalus)

- Buildup of fluid between the skull and brain (subdural effusion)

- Inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis)

- Seizures

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call 911 or the local emergency number or go to an emergency room if you suspect meningitis in a young child who has the following symptoms:

- Feeding difficulties

- High-pitched cry

- Irritability

- Persistent unexplained fever

Meningitis can quickly become a life-threatening illness.

Prevention

Close contacts in the same household, school, or day care center should be watched for early signs of the disease as soon as the first person is diagnosed. All family and close contacts of this person should begin antibiotic treatment as soon as possible to prevent spread of the infection. Ask your provider about this during the first visit.

Always use good hygiene habits, such as washing hands before and after changing a diaper or after using the toilet.

Vaccines for meningococcus are effective for controlling spread. They are currently recommended for:

- Adolescents

- College students in their first year living in dormitories

- Military recruits

- Travelers to certain parts of the world

Although rare, people who have been vaccinated can still develop the infection.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Meningitis. About bacterial meningitis. www.cdc.gov/meningitis/about/bacterial-meningitis.html. Updated January 9, 2024. Accessed June 17, 2024.

Pollard AJ, Sadarangani M. Neisseria meningitides (meningococcus). In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 218.

Stephens DS. Neisseria meningitidis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 211.

Meninges of the brain - illustration

Meninges of the brain

illustration

Meninges of the spine - illustration

Meninges of the spine

illustration

Meningococcal lesions on the back - illustration

Meningococcal lesions on the back

illustration

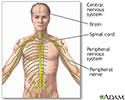

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system - illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system

illustration

CSF cell count - illustration

CSF cell count

illustration

Brudzinski's sign of meningitis - illustration

Brudzinski's sign of meningitis

illustration

Kernig's sign of meningitis - illustration

Kernig's sign of meningitis

illustration

Meninges of the brain - illustration

Meninges of the brain

illustration

Meninges of the spine - illustration

Meninges of the spine

illustration

Meningococcal lesions on the back - illustration

Meningococcal lesions on the back

illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system - illustration

Central nervous system and peripheral nervous system

illustration

CSF cell count - illustration

CSF cell count

illustration

Brudzinski's sign of meningitis - illustration

Brudzinski's sign of meningitis

illustration

Kernig's sign of meningitis - illustration

Kernig's sign of meningitis

illustration

Review Date: 9/10/2022

Reviewed By: Jatin M. Vyas, MD, PhD, Associate Professor in Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Associate in Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.