Strabismus

Crossed eyes; Esotropia; Exotropia; Hypotropia; Hypertropia; Squint; Walleye; Misalignment of the eyes

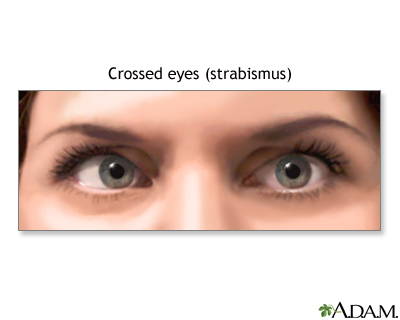

Strabismus is a disorder in which both eyes do not line up in the same direction. Therefore, they do not look at the same object at the same time. The most common form of strabismus is known as "crossed eyes."

Causes

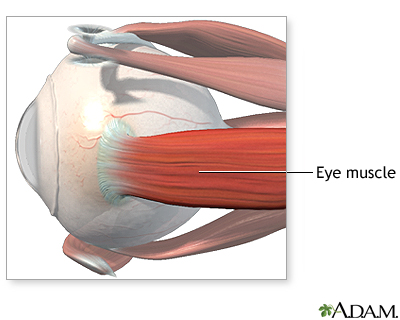

Six different muscles surround each eye and work "as a team." This allows both eyes to focus on the same object.

In someone with strabismus, these muscles do not work together. As a result, one eye looks at one object, while the other eye turns in a different direction and looks at another object.

When this occurs, two different images are sent to the brain -- one from each eye. This confuses the brain. In children, the brain may learn to ignore (suppress) the image from the weaker eye.

If the strabismus is not treated, the eye that the brain ignores will never see well. This loss of vision is called amblyopia. Another name for amblyopia is "lazy eye." Sometimes lazy eye is present first, and it causes strabismus.

In most children with strabismus, the cause is unknown. In more than one half of these cases, the problem is present at or shortly after birth. This is called congenital strabismus.

Most of the time, the problem has to do with muscle control, and not with muscle strength.

Other disorders associated with strabismus in children include:

- Apert syndrome

- Cerebral palsy

- Congenital rubella

- Hemangioma near the eye during infancy

- Incontinentia pigmenti syndrome

- Noonan syndrome

- Prader-Willi syndrome

- Retinopathy of prematurity

- Retinoblastoma

- Traumatic brain injury

- Trisomy 18

Strabismus that develops in adults can be caused by:

- Botulism

- Diabetes (causes a condition known as acquired paralytic strabismus)

- Graves disease

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Injury to the eye

- Shellfish poisoning

- Stroke

- Traumatic brain injury

- Vision loss from any eye disease or injury

A family history of strabismus is a risk factor. Farsightedness may be a contributing factor, often in children. Any other disease that causes vision loss may also cause strabismus.

Symptoms

Symptoms of strabismus may be present all the time or may come and go. Symptoms can include:

- Crossed eyes

- Double vision

- Eyes that do not aim in the same direction

- Uncoordinated eye movements (eyes do not move together)

- Loss of vision or depth perception

It is important to note that children may never be aware of double vision. This is because amblyopia can develop quickly.

Exams and Tests

The health care provider will do a physical exam. This exam includes a detailed examination of the eyes.

The following tests will be done to determine how much the eyes are out of alignment.

- Corneal light reflex

- Cover/uncover test

- Retinal exam

- Standard ophthalmic exam

- Visual acuity

A brain and nervous system (neurological) exam will also be done.

Treatment

The first step in treating strabismus in children is to prescribe glasses, if needed.

Next, amblyopia or lazy eye must be treated. A patch is placed over the better eye. This forces the brain to use the weaker eye and get better vision.

Your child may not like wearing a patch or eyeglasses. A patch forces the child to see through the weaker eye at first. However, it is very important to use the patch or eyeglasses as directed.

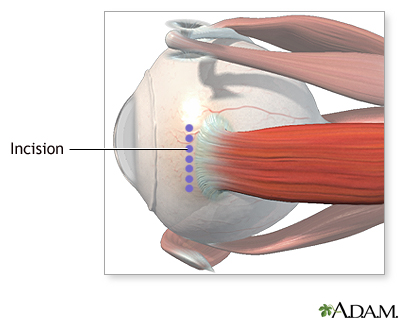

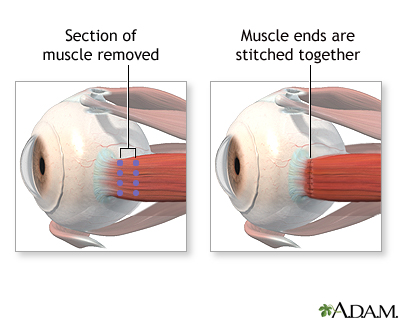

Eye muscle surgery may be needed if the eyes still do not move correctly. Different muscles in the eye will be made stronger or weaker. To strengthen a muscle, it is removed from the eye, shortened, then reattached. To weaken a muscle, it is removed from the eye and reattached further toward the back of the eye. Often in adults, an adjustable suture method is used so that the final adjustment of the position of the weakened muscle is made with the person awake and looking at a target. This has been shown to be more accurate.

Eye muscle repair surgery does not fix the poor vision of a lazy eye. Muscle surgery will fail if amblyopia has not been treated. A child may still have to wear glasses after surgery. Surgery is more often successful if done when the child is younger.

Adults with mild strabismus that comes and goes may do well with glasses. Eye muscle exercises may help keep the eyes straight. More severe forms will require surgery to straighten the eyes. If strabismus has occurred because of vision loss, the vision loss will need to be corrected before strabismus surgery can be successful.

Outlook (Prognosis)

After surgery, the eyes may look straight, but vision problems can remain.

The child may still have reading problems in school. Adults may have a hard time driving. Impaired vision may affect the ability to play sports.

In most cases, the problem can be corrected if identified and treated early. Permanent vision loss in one eye may occur if treatment is delayed. If amblyopia is not treated by about age 11, it is likely to become permanent, However, new research suggests that a special form of patching and certain medicines may help to improve amblyopia, even in adults. About one third of children with strabismus will develop amblyopia.

Many children will get strabismus or amblyopia again. Therefore, the child will need to be monitored closely.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Strabismus should be evaluated promptly. Contact your provider or eye doctor if your child:

- Appears to be cross-eyed

- Complains of double vision

- Has difficulty seeing

Note: Learning and school problems can sometimes be due to a child's inability to see the blackboard or reading material.

References

American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus website. Strabismus. aapos.org/browse/glossary/entry?GlossaryKey=f95036af-4a14-4397-bf8f-87e3980398b4. Updated October 7, 2020. Accessed November 10, 2022.

Heidary G, Aakalu VK, Binenbaum G, et al. Adjustable sutures in the treatment of strabismus: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(1):100-109. PMID: 34446304 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34446304/.

Nischal KK. Ophthalmology. In: Zitelli BJ, McIntire SC, Nowalk AJ, Garrison J, eds. Zitelli and Davis' Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023:chap 20.

Olitsky SE, Marsh JD. Disorders of eye movement and alignment. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 641.

Rucker JC, Lavin PJM. Neuro-ophthalmology: ocular motor system. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 18.

Salmon JF. Strabismus. In: Salmon JF, ed. Kanski's Clinical Ophthalmology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 18.

Yen M-Y. Therapy for amblyopia: a newer perspective. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2017;7(2):59-61. PMID: 29018758 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29018758/.

Review Date: 8/22/2022

Reviewed By: Franklin W. Lusby, MD, Ophthalmologist, Lusby Vision Institute, La Jolla, CA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.