Kidney stones

Renal calculi; Nephrolithiasis; Stones - kidney; Calcium oxalate - stones; Cystine - stones; Struvite - stones; Uric acid - stones; Urinary lithiasis

A kidney stone is a solid mass made up of tiny crystals. One or more stones can be in the kidney or ureter at the same time.

Causes

Kidney stones are common. Some types run in families. They may occur at any age, including in premature infants.

There are different types of kidney stones. The cause depends on the type of stone.

Stones can form when urine contains too much of certain substances that form crystals. These crystals can develop into stones over weeks or months.

- Calcium stones are most common. They are most likely to occur in men between ages 20 to 30. Calcium can combine with other substances to form the stone.

- Oxalate is the most common of these substances. Oxalate is present in certain foods such as spinach. It is also found in vitamin C supplements. Diseases of the small intestine increase your risk for these stones.

Calcium stones can also form by combining with phosphate or carbonate.

Other types of stones include:

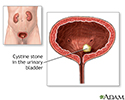

- Cystine stones can form in people who have cystinuria. This disorder runs in families. It affects both men and women.

- Struvite stones are mostly found in men or women who have repeated urinary tract infections. These stones can grow very large and can block the kidney, ureter, or bladder.

- Uric acid stones are more common in men than in women. They can occur with gout or after receiving chemotherapy for some types of cancer.

- Other substances, such as certain medicines, also can form stones.

The biggest risk factor for kidney stones is not drinking enough fluids. Kidney stones are more likely to occur if you make less than 1 liter (32 ounces) of urine a day.

Symptoms

You may not have symptoms until the stone moves down the tube (ureters) through which urine empties into your bladder. When this happens, the stone can block the flow of urine out of the kidneys, causing pain.

The main symptom is severe pain that starts and stops suddenly:

- Pain may be felt in the belly area or side of the back.

- Pain may move to the groin area (groin pain), testicles (testicle pain) in men, and labia (vaginal pain) in women.

Other symptoms can include:

Exams and Tests

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. The belly area (abdomen) or back might feel sore.

Tests that may be done include:

- Blood tests to check calcium, phosphorus, uric acid, and electrolyte levels

- Kidney function tests

- Urinalysis to check for crystals and red blood cells in urine

- Examination of the stone to determine the type

Stones or a blockage can be seen on:

- Abdominal CT scan

- Abdominal x-rays

- Kidney ultrasound

- Retrograde pyelogram

Treatment

Treatment depends on the type of stone and the severity of your symptoms.

Kidney stones that are small most often pass through your system on their own.

- Your urine should be strained so the stone can be saved and tested.

- Drink at least 6 to 8 glasses of water per day to produce a large amount of urine. This will help the stone pass.

- Pain can be very bad. Over-the-counter pain medicines (for example, ibuprofen and naproxen), either alone or along with narcotics, can be very effective.

Some people with severe pain from kidney stones need to stay in the hospital. You may need to get fluids through an IV into your vein.

For some types of stones, your provider may prescribe medicine to prevent stones from forming or help stones pass through your urinary system. These medicines can include:

- Allopurinol (for calcium oxalate or some uric acid stones)

- Antibiotics (for struvite stones)

- Phosphate solutions

- Potassium citrate

- Water pills (thiazide diuretics)

- Tamsulosin to relax the ureter and help the stone pass

Surgery is often needed if:

- The stone is too large to pass on its own.

- The stone is growing.

- The stone is blocking urine flow and causing an infection or kidney damage.

- The pain cannot be controlled.

- If there is a urinary tract infection or fever.

Today, most treatments are much less invasive than in the past.

- Lithotripsy is used to remove stones slightly smaller than one half an inch (1.25 centimeters) that are located in the kidney or ureter. It uses sound or shock waves to break up stones into tiny fragments. Then, the stone fragments leave the body in the urine. It is also called extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy or ESWL.

- Procedures performed by passing a special instrument through a small surgical cut in your skin on your back and into your kidney or ureters are used for large stones, or when the kidneys or surrounding areas are incorrectly formed. The stone is removed with a tube (endoscope).

- Ureteroscopy may be used for stones in the lower urinary tract. A laser is used to break up the stone.

- Rarely, open surgery (nephrolithotomy) may be needed if other methods do not work or are not possible.

Talk to your provider about what treatment options may work for you.

You will need to take self-care steps. Which steps you take depend on the type of stone you have, but they may include:

- Drinking extra water and other liquids

- Eating more of some foods and cutting back on other foods

- Taking medicines to help prevent stones

- Taking medicines to help you pass a stone (anti-inflammatory drugs, alpha-blockers)

Outlook (Prognosis)

Kidney stones are painful, but most of the time can be removed from the body without causing lasting damage.

Kidney stones often come back. This occurs more often if the cause is not found and treated.

You are at risk for:

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Kidney damage or scarring if treatment is delayed for too long

Possible Complications

Complications of kidney stones may include the obstruction of the ureter (acute unilateral obstructive uropathy).

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Contact your provider if you have symptoms of a kidney stone:

- Severe pain in your back or side that will not go away

- Blood in your urine

- Fever and chills

- Vomiting

- Urine that smells bad or looks cloudy

- A burning feeling when you urinate

If you have been diagnosed with blockage from a stone, passage must be confirmed either by capture in a strainer during urination or by follow-up x-ray. Being pain free does not confirm that the stone has passed.

Prevention

If you have a history of stones:

- Drink plenty of fluids (6 to 8 glasses of water per day) to produce enough urine.

- You may need to take medicine or make changes to your diet for some types of stones.

- Your provider may want to do blood and urine tests to help determine the proper prevention steps.

References

American Urological Association website. Medical management of kidney stones (2019). www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/kidney-stones-medical-mangement-guideline. Updated 2019. Accessed July 30, 2024.

American Urological Association website. Surgical management of stones: AUA/Endourology Society guideline (2016). www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/kidney-stones-surgical-management-guideline. Updated 2016. Accessed July 30, 2024.

Bushinsky DA. Nephrolithiasis. In: Goldman L, Cooney KA, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 27th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2024:chap 111.

Miller NL, Borofsky MS. Evaluation and medical management of urinary lithiasis. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 92.

Kidney stones

Animation

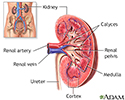

Kidney anatomy - illustration

Kidney anatomy

illustration

Kidney - blood and urine flow - illustration

Kidney - blood and urine flow

illustration

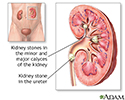

Nephrolithiasis - illustration

Nephrolithiasis

illustration

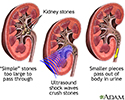

Lithotripsy procedure - illustration

Lithotripsy procedure

illustration

Cystinuria - illustration

Cystinuria

illustration

Kidney pain - illustration

Kidney pain

illustration

Kidney anatomy - illustration

Kidney anatomy

illustration

Kidney - blood and urine flow - illustration

Kidney - blood and urine flow

illustration

Nephrolithiasis - illustration

Nephrolithiasis

illustration

Lithotripsy procedure - illustration

Lithotripsy procedure

illustration

Cystinuria - illustration

Cystinuria

illustration

Kidney pain - illustration

Kidney pain

illustration

Review Date: 3/31/2024

Reviewed By: Sovrin M. Shah, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.